An Investigation of Feminist Claims about Rape. As a crime against the person, rape is uniquely horrible in its long-term effects. The anguish it brings is often followed by an abiding sense of fear and shame. Discussions of the data on rape inevitably seem callous. How can one quantify the sense of deep violation behind the statistics? Terms like incidence and prevalence are statistical jargon; once we use them, we necessarily abstract ourselves from the misery. Yet, it remains clear that to arrive at intelligent policies and strategies to decrease the occurrence of rape, we have no alternative but to gather and analyze data, and to do so does not make us callous. Truth is no enemy to compassion, and falsehood is no friend.

Some feminists routinely refer to American society as a “rape culture.” Yet estimates on the prevalence of rape vary wildly. According to the FBI Uniform Crime Report, there were 102,560 reported rapes or attempted rapes in 1990.[1] The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimates that 130,000 women were victims of rape in 1990.[2] A Harris poll sets the figure at 380,000 rapes or sexual assaults for 1993.[3] According to a study by the National Victims Center, there were 683,000 completed forcible rapes in 1990.[4] The Justice Department says that 8 percent of all American women will be victims of rape or attempted rape in their lifetime. The radical feminist legal scholar Catharine MacKinnon, however, claims that “by conservative definition [rape] happens to almost half of all women at least once in their lives.”[5]

Who is right? Feminist activists and others have plausibly argued that the relatively low figures of the FBI and the Bureau of Justice Statistics are not trustworthy. The FBI survey is based on the number of cases reported to the police, but rape is among the most underreported of crimes. The Bureau of Justice Statistics National Crime Survey is based on interviews with 100,000 randomly selected women. It, too, is said to be flawed because the women were never directly questioned about rape. Rape was discussed only if the woman happened to bring it up in the course of answering more general questions about criminal victimization. The Justice Department has changed its method of questioning to meet this criticism, so we will know in a year or two whether this has a significant effect on its numbers. Clearly, independent studies on the incidence and prevalence of rape are badly needed. Unfortunately, research groups investigating in this area have no common definition of rape, and the results so far have led to confusion and acrimony.

Rape: “Normal Male Behavior”

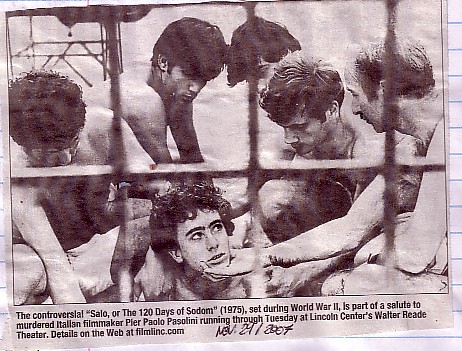

Of the rape studies by nongovernment groups, the two most frequently cited are the 1985 Ms. magazine report by Mary Koss and the 1992 National Women’s Study by Dr. Dean Kilpatrick of the Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center at the Medical School of South Carolina. In 1982, Mary Koss, then a professor of psychology at Kent State University in Ohio, published an article on rape in which she expressed the orthodox gender feminist view that “rape represents an extreme behavior but one that is on a continuum with normal male behavior within the culture” (my emphasis).[6] Some well-placed feminist activists were impressed by her. As Koss tells it, she received a phone call out of the blue inviting her to lunch with Gloria Steinem.[7] For Koss, the lunch was a turning point. Ms. magazine had decided to do a national rape survey on college campuses, and Koss was chosen to direct it. Koss’s findings would become the most frequently cited research on women’s victimization, not so much by established scholars in the field of rape research as by journalists, politicians, and activists.

Koss and her associates interviewed slightly more than three thousand college women, randomly selected nationwide.[8] The young women were asked ten questions about sexual violation. These were followed by several questions about the precise nature of the violation. Had they been drinking? What were their emotions during and after the event? What forms of resistance did they use? How would they label the event? Koss counted anyone who answered affirmatively to any of the last three questions as having been raped:

8. Have you had sexual intercourse when you didn’t want to because a man gave you alcohol or drugs?

9. Have you had sexual intercourse when you didn’t want to because a man threatened or used some degree of physical force (twisting your arm, holding you down, etc.) to make you?

10. Have you had sexual acts (anal or oral intercourse or penetration by objects other than the penis) when you didn’t want to because a man threatened or used some degree of physical force (twisting your arm, holding you down, etc.) to make you?

Koss and her colleagues concluded that 15.4 percent of respondents had been raped, and that 12.1 percent had been victims of attempted rape.[9] Thus, a total of 27.5 percent of the respondents were determined to have been victims of rape or attempted rape because they gave answers that fit Koss’s criteria for rape (penetration by penis, finger, or other object under coercive influence such as physical force, alcohol, or threats). However, that is not how the so-called rape victims saw it.

Only about a quarter of the women Koss calls rape victims labeled what happened to them as rape. According to Koss, the answers to the follow-up questions revealed that “only 27 percent” of the women she counted as having been raped labeled themselves as rape victims.[10] Of the remainder, 49 percent said it was “miscommunication,” 14 percent said it was a “crime but not rape,” and 11 percent said they “don’t feel victimized.”[11]

In line with her view of rape as existing on a continuum of male sexual aggression, Koss also asked: “Have you given in to sex play (fondling, kissing, or petting, but not intercourse) when you didn’t want to because you were overwhelmed by a man’s continual arguments and pressure?” To this question, 53.7 percent responded affirmatively, and they were counted as having been sexually victimized.

The Koss study, released in 1988, became known as the Ms. Report. Here is how the Ms. Foundation characterizes the results: “The Ms. project-the largest scientific investigation ever undertaken on the subject-revealed some disquieting statistics, including this astonishing fact: one in four female respondents had an experience that met the legal definition of rape or attempted rape.”[12]

The Official “One in Four” Figure

“One in four” has since become the official figure on women’s rape victimization cited in women’s studies departments, rape crisis centers, women’s magazines, and on protest buttons and posters. Susan Faludi defended it in a Newsweek story on sexual correctness.[13] Naomi Wolf refers to it in The Beauty Myth, calculating that acquaintance rape is “more common than lefthandedness, alcoholism, and heart attacks.”[14] “One in four” is chanted in “Take Back the Night” processions, and it is the number given in the date rape brochures handed out at freshman orientation at colleges and universities around the country.[15] Politicians, from Senator Joseph Biden of Delaware, a Democrat, to Republican Congressman Jim Ramstad of Minnesota, cite it regularly, and it is the primary reason for the Title IV, “Safe Campuses for Women” provision of the Violence Against Women Act of 1993, which provides twenty million dollars to combat rape on college campuses.[16]

When Neil Gilbert, a professor at Berkeley’s School of Social Welfare, first read the “one in four” figure in the school newspaper, he was convinced it could not be accurate. The results did not tally with the findings of almost all previous research on rape. When he read the study he was able to see where the high figures came from and why Koss’s approach was unsound.

He noticed, for example, that Koss and her colleagues counted as victims of rape any respondent who answered “yes” to the question “Have you had sexual intercourse when you didn’t want to because a man gave you alcohol or drugs?” That opened the door wide to regarding as a rape victim anyone who regretted her liaison of the previous night. If your date mixes a pitcher of margaritas and encourages you to drink with him and you accept a drink, have you been “administered” an intoxicant, and has your judgment been impaired? Certainly, if you pass out and are molested, one would call it rape. But if you drink and, while intoxicated, engage in sex that you later come to regret, have you been raped? Koss does not address these questions specifically, she merely counts your date as a rapist and you as a rape statistic if you drank with your date and regret having had sex with him. As Gilbert points out, the question, as Koss posed it, is far too ambiguous:

What does having sex “because” a man gives you drugs or alcohol signify? A positive response does not indicate whether duress, intoxication, force, or the threat of force were present; whether the woman’s judgment or control were substantially impaired; or whether the man purposefully got the woman drunk in order to prevent her resistance to sexual advances…. While the item could have been clearly worded to denote “intentional incapacitation of the victim,” as the question stands it would require a mind reader to detect whether any affirmative response corresponds to this legal definition of rape.[17]

Koss, however, insisted that her criteria conformed with the legal definitions of rape used in some states, and she cited in particular the statute on rape of her own state, Ohio: “No person shall engage in sexual conduct with another person . . . when . . . for the purpose of preventing resistance the offender substantially impairs the other person’s judgment or control by administering any drug or intoxicant to the other person” (Ohio revised code 1980, 2907.01A, 2907.02).[18]

The Blade Cuts Deep

Two reporters from the Blade a small, progressive Toledo, Ohio, newspaper that has won awards for the excellence of its investigative articles-were also not convinced that the “one in four” figure was accurate. They took a close look at Koss’s study and at several others that were being cited to support the alarming tidings of widespread sexual abuse on college campuses. In a special three-part series on rape called “The Making of an Epidemic,” published in October 1992, the reporters, Nara Shoenberg and Sam Roe, revealed that Koss was quoting the Ohio statute in a very misleading way: she had stopped short of mentioning the qualifying clause of the statute, which specifically excludes “the situations where a person plies his intended partner with drink or drugs in hopes that lowered inhibition might lead to a liaison.”[19] Koss now concedes that question eight was badly worded. Indeed, she told the Blade reporters, “At the time I viewed the question as legal; I now concede that it’s ambiguous.”[20] That concession should have been followed by the admission that her survey may be inaccurate by a factor of two: for, as Koss herself told the Blade, once you remove the positive responses to question eight, the finding that one in four college women is a victim of rape or attempted rape drops to one in nine.[21] But as we shall see, this figure too is unacceptably high.

For Gilbert, the most serious indication that something was basically awry in the Ms./Koss study was that the majority of women she classified as having been raped did not believe they had been raped. Of those Koss counts as having been raped, only 27 percent thought they had been; 73 percent did not say that what happened to them was rape. In effect, Koss and her followers present us with a picture of confused young women overwhelmed by threatening males who force their attentions on them during the course of a date but are unable or unwilling to classify their experience as rape. Does that picture fit the average female undergraduate? For that matter, does it plausibly apply to the larger community? As the journalist Cathy Young observes, “Women have sex after initial reluctance for a number of reasons . . . fear of being beaten up by their dates is rarely reported as one of them.”[22]

Katie Roiphe, a graduate student in English at Princeton and author of The Morning After: Sex, Fear, and Feminism on Campus, argues along similar lines when she claims that Koss had no right to reject the judgment of the college women who didn’t think they were raped. But Katha Pollitt of The Nation defends Koss, pointing out that in many cases people are wronged without knowing it. Thus we do not say that “victims of other injustices-fraud, malpractice, job discrimination-have suffered no wrong as long as they are unaware of the law.”[23]

Pollitt’s analogy is faulty, however. If Jane has ugly financial dealings with Tom and an expert explains to Jane that Tom has defrauded her, then Jane usually thanks the expert for having enlightened her about the legal facts. To make her case, Pollitt would have to show that the rape victims who were unaware that they were raped would accept Koss’s judgment that they really were. But that has not been shown; Koss did not enlighten the women she counts as rape victims, and they did not say “now that you explain it, we can see we were.”

Koss and Pollitt make a technical (and in fact dubious) legal point: women are ignorant about what counts as rape. Roiphe makes a straightforward human point: the women were there, and they know best how to judge what happened to them. Since when do feminists consider “law” to override women’s experience?

Koss also found that 42 percent of those she counted as rape victims went on to have sex with their attackers on a later occasion. For victims of attempted rape, the figure for subsequent sex with reported assailants was 35 percent. Koss is quick to point out that “it is not known if [the subsequent sex] was forced or voluntary” and that most of the relationships “did eventually break up subsequent to the victimization.”[24] But of course, most college relationships break up eventually for one reason or another. Yet, instead of taking these young women at their word, Koss casts about for explanations of why so many “raped” women would return to their assailants, implying that they may have been coerced. She ends by treating her subjects’ rejection of her findings as evidence that they were confused and sexually naive.

There is a more respectful explanation. Since most of those Koss counts as rape victims did not regard themselves as having been raped, why not take this fact and the fact that so many went back to their partners as reasonable indications that they had not been raped to begin with?

The Toledo reporters calculated that if you eliminate the affirmative responses to the alcohol or drugs question, and also subtract from Koss’s results the women who did not think they were raped, her one in four figure for rape and attempted rape “drops to between one in twenty-two and one in thirty-three.”[25]

The “One in Eight” Study

The other frequently cited nongovernment rape study, the National Women’s Study, was conducted by Dean Kilpatrick. From an interview sample of 4,008 women, the study projected that there were 683,000 rapes in 1990. As to prevalence, it concluded that “in America, one out of every eight adult women, or at least 12.1 million American women, has been the victim of forcible rape sometime in her lifetime.”[26]

Unlike the Koss report, which tallied rape attempts as well as rapes, the Kilpatrick study focused exclusively on rape. Interviews were conducted by phone, by female interviewers. A woman who agreed to become part of the study heard the following from the interviewer: “Women do not always report such experiences to police or discuss them with family or friends.

The person making the advances isn’t always a stranger, but can be a friend, boyfriend, or even a family member. Such experiences can occur anytime in a woman’s life-even as a child.”[27] Pointing out that she wants to hear about any such experiences “regardless of how long ago it happened or who made the advances,” the interviewer proceeds to ask four questions:

1. Has a man or boy ever made you have sex by using force or threatening to harm you or someone close to you? Just so there is no mistake, by sex we mean putting a penis in your vagina.

2. Has anyone ever made you have oral sex by force or threat of harm? Just so there is no mistake, by oral sex we mean that a man or boy put his penis in your mouth or somebody penetrated your vagina or anus with his mouth or tongue.

3. Has anyone ever made you have anal sex by force or threat of harm?

4. Has anyone ever put fingers or objects in your vagina or anus against your will by using force or threat?

Any woman who answered yes to any one of the four questions was classified as a victim of rape.

This seems to be a fairly straightforward and well-designed survey that provides a window into the private horror that many women, especially very young women, experience. One of the more disturbing findings of the survey was that 61 percent of the victims said they were seventeen or younger when the rape occurred.

There is, however, one flaw that affects the significance of Kilpatrick’s findings. An affirmative answer to any one of the first three questions does reasonably put one in the category of rape victim. The fourth is problematic, for it includes cases in which a boy penetrated a girl with his finger, against her will, in a heavy petting situation. Certainly the boy behaved badly. But is he a rapist? Probably neither he nor his date would say so. Yet, the survey classifies him as a rapist and her as a rape victim.

I called Dr. Kilpatrick and asked him about the fourth question. “Well,” he said, “if a woman is forcibly penetrated by an object such as a broomstick, we would call that rape.”

“So would I,” I said. “But isn’t there a big difference between being violated by a broomstick and being violated by a finger?” Dr. Kilpatrick acknowledged this: “We should have split out fingers versus objects,” he said. Still, he assured me that the question did not significantly affect the outcome. But I wondered. The study had found an epidemic of rape among teenagers-just the age group most likely to get into situations like the one I have described.

A Serious Discrepancy

The more serious worry is that Kilpatrick’s findings, and many other findings on rape, vary wildly unless the respondents are explicitly asked whether they have been raped. In 1993, Louis Harris and Associates did a telephone survey and came up with quite different results. Harris was commissioned by the Commonwealth Fund to do a study of women’s health. As we shall see, their high figures on women’s depression and psychological abuse by men caused a stir.[28] But their finding on rape went altogether unnoticed. Among the questions asked of its random sample population of 2,500 women was, “In the last five years, have you been a victim of a rape or sexual assault?” Two percent of the respondents said yes; 98 percent said no. Since attempted rape counts as sexual assault, the combined figures for rape and attempted rape would be 1.9 million over five years or 380,000 for a single year. Since there are approximately twice as many attempted rapes as completed rapes, the Commonwealth/ Harris figure for completed rapes would come to approximately 190,000. That is dramatically lower than Kilpatrick’s finding of 683,000 completed forcible rapes.

The Harris interviewer also asked a question about acquaintance and marital rape that is worded very much like Kilpatrick’s and Koss’s: “In the past year, did your partner ever try to, or force you to, have sexual relations by using physical force, such as holding you down, or hitting you, or threatening to hit you, or not?”[29] Not a single respondent of the Harris poll’s sample answered yes.

How to explain the discrepancy? True, women are often extremely reluctant to talk about sexual violence that they have experienced. But the Harris pollsters had asked a lot of other awkward personal questions to which the women responded with candor: six percent said they had considered suicide, five percent admitted to using hard drugs, 10 percent said they had been sexually abused when they were growing up. I don’t have the answer, though it seems obvious to me that such wide variances should make us appreciate the difficulty of getting reliable figures on the risk of rape from the research. That the real risk should be known is obvious. The Blade reporters interviewed students on their fears and found them anxious and bewildered. “It makes a big difference if it’s one in three or one in 50,” said April Groff of the University of Michigan, who says she is “very scared.” “I’d have to say, honestly, I’d think about rape a lot less if I knew the number was one in 50.”[30]

When the Blade reporters asked Kilpatrick why he had not asked women whether they had been raped, he told them there had been no time in the thirty-five-minute interview. “That was probably something that ended up on the cutting-room floor.”[31] But Kilpatrick’s exclusion of such a question resulted in very much higher figures. When pressed about why he omitted it from a study for which he had received a million- dollar federal grant, he replied, “If people think that is a key question, let them get their own grant and do their own study.”[32]

Kilpatrick had done an earlier study in which respondents were explicitly asked whether they had been raped. That study showed a relatively low prevalence of five percent-one in twenty-and it got very little publicity.[33] Kilpatrick subsequently abandoned his former methodology in favor of the Ms./Koss method, which allows the surveyor to decide whether a rape occurred. Like Koss, he used an expanded definition of rape (both include penetration by a finger). Kilpatrick’s new approach yielded him high numbers (one in eight), and citations in major newspapers around the country. His graphs were reproduced in Time magazine under the heading, “Unsettling Report on an Epidemic of Rape.”[34] Now he shares with Koss the honor of being a principal expert cited by media, politicians, and activists.

There are many researchers who study rape victimization, but their relatively low figures generate no headlines. The reporters from the Blade interviewed several scholars whose findings on rape were not sensational but whose research methods were sound and were not based on controversial definitions. Eugene Kanin, a retired professor of sociology from Purdue University and a pioneer in the field of acquaintance rape, is upset by the intrusion of politics into the field of inquiry: “This is highly convoluted activism rather than social science research.”[35] Professor Margaret Gordon of the University of Washington did a study in 1981 that came with relatively low figures for rape (one in fifty). She tells of the negative reaction to her findings: “There was some pressure-at least I felt pressure-to have rape be as prevalent as possible . . .. I’m a pretty strong feminist, but one of the things I was fighting was that the really avid feminists were trying to get me to say that things were worse than they really are.”[36]

Dr. Linda George of Duke University also found relatively low rates of rape (one in seventeen), even though she asked questions very close to Kilpatrick’s. She told the Blade she is concerned that many of her colleagues treat the high numbers as if they are “cast in stone.”[37] Dr. Naomi Breslau, director of research in the psychiatry department at the Henry Ford Health Science Center in Detroit, who also found low numbers, feels that it is important to challenge the popular view that higher numbers are necessarily more accurate. Dr. Breslau sees the need for a new and more objective program of research: “It’s really an open question. . . . We really don’t know a whole lot about it.”[38]

“Rape Crisis” Hysteria: “Potential Survivors” and “Potential Rapists”

An intrepid few in the academy have publicly criticized those who have proclaimed a “rape crisis” for irresponsibly exaggerating the problem and causing needless anxiety. Camille Paglia claims that they have been especially hysterical about date rape: “Date rape has swelled into a catastrophic cosmic event, like an asteroid threatening the earth in a 50’s science fiction film.”[39] She bluntly rejects the contention that “‘No’ always means no . . ..’No’ has always been, and always will be, part of the dangerous, alluring courtship ritual of sex and seduction, observable even in the animal kingdom.”[40]

Paglia’s dismissal of date rape hype infuriates campus feminists, for whom the rape crisis is very real. On most campuses, date-rape groups hold meetings, marches, rallies. Victims are “survivors,” and their friends are “co-survivors” who also suffer and need counseling.[41] At some rape awareness meetings, women who have not yet been date raped are referred to as “potential survivors.” Their male classmates are “potential rapists.”[42]

Has date rape in fact reached critical proportions on the college campus? Having heard about an outbreak of rape at Columbia University, Peter Hellman of New York magazine decided to do a story about it.[43] To his surprise, he found that campus police logs showed no evidence of it whatsoever. Only two rapes were reported to the Columbia campus police in 1990, and in both cases, charges were dropped for lack of evidence. Hellman checked the figures at other campuses and found that in 1990 fewer than one thousand rapes were reported to campus security on college campuses in the entire country.[44] That works out to fewer than one-half of one rape per campus. Yet despite the existence of a rape crisis center at St. Luke’s-Roosevelt Hospital two blocks from Columbia University, campus feminists pressured the administration into installing an expensive rape crisis center inside the university. Peter Hellman describes a typical night at the center in February 1992: “On a recent Saturday night, a shift of three peer counselors sat in the Rape Crisis Center-one a backup to the other two. . . . Nobody called; nobody came. As if in a firehouse, the three women sat alertly and waited for disaster to strike. It was easy to forget these were the fading hours of the eve of Valentine’s Day.”[45]

In The Morning After, Katie Roiphe describes the elaborate measures taken to prevent sexual assaults at Princeton. Blue lights have been installed around the campus, freshman women are issued whistles at orientation. There are marches, rape counseling sessions, emergency telephones. But as Roiphe tells it, Princeton is a very safe town, and whenever she walked across a deserted golf course to get to classes, she was more afraid of the wild geese than of a rapist. Roiphe reports that between 1982 and 1993 only two rapes were reported to the campus police. And, when it comes to violent attacks in general, male students are actually more likely to be the victims. Roiphe sees the campus rape crisis movement as a phenomenon of privilege: these young women have had it all, and when they find out that the world can be dangerous and unpredictable, they are outraged:

Many of these girls [in rape marches] came to Princeton from Milton and Exeter. Many of their lives have been full of summers in Nantucket and horseback-riding lessons. These are women who have grown up expecting fairness, consideration, and politeness.[46]

Serious Misallocation of Funds

The Blade story on rape is unique in contemporary journalism because the authors dared to question the popular feminist statistics on this terribly sensitive problem. But to my mind, the important and intriguing story they tell about unreliable advocacy statistics is overshadowed by the even more important discoveries they made about the morally indefensible way that public funds for combatting rape are being allocated. Schoenberg and Roe studied Toledo neighborhoods and calculated that women in the poorer areas were nearly thirty times more likely to be raped than those in the wealthy areas. They also found that campus rape rates were 30 times lower than the rape rates for the general population of 18-to 24-year-olds in Toledo. The attention and the money are disproportionately going to those least at risk. According to the Blade reporters:

Across the nation, public universities are spending millions of dollars a year on rapidly growing programs to combat rape. Videos, self-defense classes, and full-time rape educators are commonplace. . . . But the new spending comes at a time when community rape programs-also dependent on tax dollars-are desperately scrambling for money to help populations at much higher risk than college students.[47]

One obvious reason for this inequity is that feminist advocates come largely from the middle class and so exert great pressure to protect their own. To render their claims plausible, they dramatize themselves as victims-survivors or “potential survivors.” Another device is to expand the definition of rape (as Koss and Kilpatrick do). Dr. Andrea Parrot, chair of the Cornell University Coalition Advocating Rape Education and author of Sexual Assault on Campus, begins her date rape prevention manual with the words, “Any sexual intercourse without mutual desire is a form of rape. Anyone who is psychologically or physically pressured into sexual contact on any occasion is as much a victim as the person who is attacked in the streets” (my emphasis).[48] By such a definition, privileged young women in our nation’s colleges gain moral parity with the real victims in the community at large. Parrot’s novel conception of rape also justifies the salaries being paid to all the new personnel in the burgeoning college date rape industry. After all, it is much more pleasant to deal with rape from an office in Princeton than on the streets of downtown Trenton.

Another reason that college women are getting a lion’s share of public resources for combatting rape is that collegiate money, though originally public, is allocated by college officials. As the Blade points out:

Public universities have multi-million dollar budgets heavily subsidized by state dollars. School officials decide how the money is spent, and are eager to address the high-profile issues like rape on campus. In contrast, rape crisis centers-nonprofit agencies that provide free services in the community-must appeal directly to federal and state governments for money.[49]

Schoenberg and Roe describe typical cases of women in communities around the country-in Madison, Wisconsin, in Columbus, Ohio, in Austin, Texas, and in Newport, Kentucky-who have been raped and have to wait months for rape counseling services.

There were three rapes reported to police at the University of Minnesota in 1992; in New York City there were close to three thousand. Minnesota students have a 24-hour rape crisis hot line of their own. In New York City, the “hot line” leads to detectives in the sex crimes unit. The Blade reports that the sponsors of the Violence Against Women Act of 1993 reflect the same bizarre priorities: “If Senator Biden has his way, campuses will get at least twenty million more dollars for rape education and prevention.” In the meantime, Gail Rawlings of the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape complains that the bill guarantees nothing for basic services, counseling, and support groups for women in the larger community: “It’s ridiculous. This bill is supposed to encourage prosecution of violence against women, land] one of the main keys is to have support for the victim. . . . I just don’t understand why [the money] isn’t there.”[50]

Because rape is the most underreported of crimes, the campus activists tell us we cannot learn the true dimensions of campus rape from police logs or hospital reports. But as an explanation of why there are so few known and proven incidents of rape on campus, that won’t do. Underreporting of sexual crimes is not confined to the campus, and wherever there is a high level of reported rape-say in poor urban communities where the funds for combatting rape are almost nonexistent-the level of underreported rape will be greater still.

No matter how you look at it, women on campus do not face anywhere near the same risk of rape as women elsewhere. The fact that college women continue to get a disproportionate and ever-growing share of the very scarce public resources allocated for rape prevention and for aid to rape victims underscores how disproportionately powerful and self-preoccupied the campus feminists are despite all their vaunted concern for “women” writ large.

Once again we see what a long way the New Feminism has come from Seneca Falls. The privileged and protected women who launched the women’s movement, as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony took pains to point out, did not regard themselves as the primary victims of gender inequity: “They had souls large enough to feel the wrongs of others without being scarified in their own flesh.” They did not act as if they had “in their own experience endured the coarser forms of tyranny resulting from unjust laws, or association with immoral and unscrupulous men.”[51] Ms. Stanton and Ms. Anthony concentrated their efforts on the Hester Vaughns and the other defenseless women whose need for gender equity was urgent and unquestionable.

Scarifying Statistics

Much of the unattractive self-preoccupation and victimology that we find on today’s campuses have been irresponsibly engendered by the inflated and scarifying “one in four” statistic on campus rape. In some cases the campaign of alarmism arouses exasperation of another kind. In an article in the New York Times Magazine, Katie Roiphe questioned Koss’s figures: “If 25 percent of my women friends were really being raped, wouldn’t I know it?”[52] She also questioned the feminist perspective on male/female relations: “These feminists are endorsing their own utopian vision of sexual relations: sex without struggle, sex without power, sex without persuasion, sex without pursuit. If verbal coercion constitutes rape, then the word rape itself expands to include any kind of sex a woman experiences as negative.”[53]

The publication of Ms. Roiphe’s piece incensed the campus feminists. “The New York Times should be shot,” railed Laurie Fink, a professor at Kenyon College.[54] “Don’t invite [Katie Roiphe] to your school if you can prevent it,” counseled Pauline Bart of the University of Illinois.[55] Gail Dines, a women’s studies professor and date rape activist from Wheelock College, called Roiphe a traitor who has sold out to the “white male patriarchy.”[56]

Other critics, such as Camille Paglia and Berkeley professor of social welfare Neil Gilbert, have been targeted for demonstrations, boycotts, and denunciations. Gilbert began to publish his critical analyses of the Ms./ Koss study in 1990.[57] Many feminist activists did not look kindly on Gilbert’s challenge to their “one in four” figure. A date rape clearinghouse in San Francisco devotes itself to “refuting” Gilbert; it sends out masses of literature attacking him. It advertises at feminist conferences with green and orange fliers bearing the headline STOP IT, BITCH! The words are not Gilbert’s, but the tactic is an effective way of drawing attention to his work. At one demonstration against Gilbert on the Berkeley campus, students chanted, “Cut it out or cut it off,” and carried signs that read, KILL NEIL GILBERT![58] Sheila Kuehl, the director of the California Women’s Law Center, confided to readers of the Los Angeles Daily Journal, “I found myself wishing that Gilbert, himself, might be raped and . . . be told, to his face, it had never happened.”[59]

The findings being cited in support of an “epidemic” of campus rape are the products of advocacy research. Those promoting the research are bitterly opposed to seeing it exposed as inaccurate. On the other hand, rape is indeed the most underreported of crimes. We need the truth for policy to be fair and effective. If the feminist advocates would stop muddying the waters we could probably get at it.

High rape numbers serve the gender feminists by promoting the belief that American culture is sexist and misogynist. But the common assumption that rape is a manifestation of misogyny is open to question. Assume for the sake of argument that Koss and Kilpatrick are right and that the lower numbers of the FBI, the Justice Department, the Harris poll, of Kilpatrick’s earlier study, and the many other studies mentioned earlier are wrong. Would it then follow that we are a “patriarchal rape culture”? Not necessarily. American society is exceptionally violent, and the violence is not specifically patriarchal or misogynist. According to International Crime Rates, a report from the United States Department of Justice “Crimes of violence (homicide, rape, and robbery) are four to nine times more frequent in the United States than they are in Europe. The U.S. crime rate for rape was . . . roughly seven times higher than the average for Europe.”[60] The incidence of rape is many times lower in such countries as Greece, Portugal, or Japan-countries far more overtly patriarchal than ours.

It might be said that places like Greece, Portugal, and Japan do not keep good records on rape. But the fact is that Greece, Portugal, and Japan are significantly less violent than we are. I have walked through the equivalent of Central Park in Kyoto at night. I felt safe, and I was safe, not because Japan is a feminist society (it is the opposite), but because crime is relatively rare. The international studies on violence suggest that patriarchy is not the primary cause of rape but that rape, along with other crimes against the person, is caused by whatever it is that makes our society among the most violent of the so-called advanced nations.

But the suggestion that criminal violence, not patriarchal misogyny, is the primary reason for our relatively high rate of rape is unwelcome to gender feminists like Susan Faludi, who insist, in the face of all evidence to the contrary, that “the highest rate of rapes appears in cultures that have the highest degree of gender inequality, where sexes are segregated at work, that have patriarchal religions, that celebrate all-male sporting and hunting rituals, i.e., a society such as us.”[61]

In the spring of 1992, Peter Jennings hosted an ABC special on the subject of rape. Catharine MacKinnon, Susan Faludi, Naomi Wolf, and Mary Koss were among the panelists, along with John Leo of U.S. News & World Report. When MacKinnon trotted out the claim that 25 percent of women are victims of rape, Mr. Leo replied, “I don’t believe those statistics. . . . That’s totally false.”[62] MacKinnon countered, “That means you don’t believe women. It’s not cooked, it’s interviews with women by people who believed them when they said it. That’s the methodology.”[63]

The accusation that Leo did not believe “women” silenced him, as it was meant to. But as we have seen, believing what women actually say is precisely not the methodology by which some feminist advocates get their incendiary statistics.

MacKinnon’s next volley was certainly on target. She pointed out that the statistics she had cited “are starting to become nationally accepted by the government.” That claim could not be gainsaid, and MacKinnon may be pardoned for crowing about it. The government, like the media, is accepting the gender feminist claims and is introducing legislation whose “whole purpose . . . is to raise the consciousness of the American public.”[64]

The words are Joseph Biden’s, and the bill to which he referred-the Violence Against Women Act-introduces the principle that violence against women is much like racial violence, calling for civil as well as criminal remedies.

Like a lynching or a cross burning, an act of violence by a man against a woman would be prosecuted as a crime of gender bias, under title three of the bill: “State and Federal criminal laws do not adequately protect against the bias element of gender-motivated crimes, which separates these crimes from acts of random violence, nor do those laws adequately provide victims of gender-motivated crimes the opportunity to vindicate their interests.”[65] Whereas ordinary violence is “random,” “violence against women” may be discriminatory in the literal sense in which we speak of a bigot as discriminating against someone because of race or religion.

Rape Litigation

Mary Koss and Sarah Buel were invited to give testimony on the subject of violence against women before the House Judiciary Committee. Dean Kilpatrick’s findings were cited. Neil Gilbert was not there; nor were any of the other scholars interviewed by the Toledo Blade.

The litigation that the bill invites gladdens the hearts of gender feminists. If we consider that a boy getting fresh in the back seat of a car may be prosecuted both as an attempted rapist and as a gender bigot who has violated his date’s civil rights, we can see why the title three provision is being hailed by radical feminists like Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin. Dworkin, who was surprised and delighted at the support the bill was getting, candidly observed that the senators “don’t understand the meaning of the legislation they pass.”[66]

Senator Biden invites us to see the bill’s potential as an instrument of moral education on a national scale. “I have become convinced . . . that violence against women reflects as much a failure of our nation’s collective moral imagination as it does the failure of our nation’s laws and regulations.”[67] Fair enough, but then why not include crimes against the elderly or children? What constitutional or moral ground is there for singling out female crime victims for special treatment under civil rights laws? Can it be that Biden and the others are buying into the gender feminist ontology of a society divided against itself along the fault line of gender?

Equity feminists are as upset as anyone else about the prevalence of violence against women, but they are not possessed of the worldview that licenses their overzealous sisters to present inflammatory but inaccurate data on male abuse.

They want social scientists to tell them the objective truth about the prevalence of rape. And because they are not committed to the view that men are arrayed against women, they are able to see violence against women in the context of what, in our country, appears to be a general crisis of violence against persons.

By distinguishing between acts of random violence and acts of violence against women, the sponsors of the Violence Against Women Act believe that they are showing sensitivity to feminist concerns. In fact, they may be doing social harm by accepting a divisive, gender-specific approach to a problem that is not caused by gender bias, misogyny, or “patriarchy”-an approach that can obscure real and urgent problems such as lesbian battering or male-on-male sexual violence.[68]

According to Stephen Donaldson, president of Stop Prison Rape, more than 290,000 male prisoners are assaulted each year. Prison rape, says Donaldson in a New York Times opinion piece, “is an entrenched tradition.” Donaldson, who was himself a victim of prison rape twenty years ago when he was incarcerated for antiwar activities, has calculated that there may be as many as 45,000 rapes every day in our prison population of 1.2 million men.

The number of rapes is vastly higher than the number of victims because the same men are often attacked repeatedly. Many of the rapes are “gang bangs” repeated day after day. To report such a rape is a terribly dangerous thing to do, so these rapes may be the most underreported of all.

No one knows how accurate Donaldson’s figures are. They seem incredible to me. But the tragic and neglected atrocities he is concerned about are not the kind whose study attracts grants from the Ford or Ms. foundations. If he is anywhere near right the incidence of male rape would be as high or higher than that of female rape.

Look to the Root Causes

Equity feminists find it reasonable to approach the problem of violence against women by addressing the root causes of the general rise in violence and the decline in civility. To view rape as a crime of gender bias (encouraged by a patriarchy that looks with tolerance on the victimization of women) is perversely to miss its true nature. Rape is perpetrated by criminals, which is to say, it is perpetrated by people who are wont to gratify themselves in criminal ways and who care very little about the suffering they inflict on others.

That most violence is male isn’t news. But very little of it appears to be misogynist. This country has more than its share of violent males, statistically we must expect them to gratify themselves at the expense of people weaker than themselves, male or female; and so they do. Gender feminist ideologues bemuse and alarm the public with inflated statistics. And they have made no case for the claim that violence against women is symptomatic of a deeply misogynist culture.

Rape is just one variety of crime against the person, and rape of women is just one subvariety. The real challenge we face in our society is how to reverse the tide of violence. How to achieve this is a true challenge to our moral imagination. It is clear that we must learn more about why so many of our male children are so violent. And it is clear we must find ways to educate all of our children to regard violence with abhorrence and contempt.

We must once again teach decency and considerateness. And this, too, must become clear: in any constructive agenda for the future, the gender feminist’s divisive social philosophy has no place.

[Researching the Rape Culture of America, reprinted with permission, was excerpted from Who Stole Feminism? (Simon & Schuster Inc., New York, 1994) by Christina Hoff Sommers, chapter 10, pp. 209-226.]

Footnotes

1. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Crime in the United States: Uniform Crime Reports (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, 1990).

2. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States 1990, (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, l992), p. 184. See also Caroline Wolf Harlow, Bureau of Justice Statistics, “Female Victims of Violent Crime” (Washington, D.C., U.S. Department of Justice, 1991), p. 7.

3. Louis Harris and Associates, “Commonwealth Fund Survey of Women’s Health” (New York: Commonwealth Fund, 1993), p. 9. What the report says is that “within the last five years, 2 percent of women 1.9 million) were raped.”

4. “Rape in America: A Report to the Nation” (Charleston, S.C.: Crime Victims Research and Treatment Center, 1992).

5. Catharine MacKinnon, “Sexuality, Pornography, and Method,” Ethics 99 January 1989): 331.

6. Mary Koss and Cheryl Oros, “Sexual Experiences Survey: A Research Instrument Investigating Sexual Aggression and Victimization,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 50, no. 3 (1982): 455.

7. Nara Schoenberg and Sam Roe, “The Making of an Epidemic,” Blade, October 10, 1993, special report, p. 4.

8. The total sample was 6,159, or whom 3,187 were females. See Mary Koss, “Hidden Rape: Sexual Aggression and Victimization in a National Sample of Students in Higher Education,” in Ann Wolbert Burgess, ed., Rape and Sexual Assault, vol. 2 (New York: Garland Publishing, 1988), p. 8.

9. Ibid., p. 10.

10. Ibid., p. 16.

11. Mary Koss, Thomas Dinero, and Cynthia Seibel, “Stranger and Acquaintance Rape,” Psychology of Women Quarterly 12 (1988): 12. See also Neil Gilbert, “Examining the Facts: Advocacy Research Overstates the Incidence of Date and Acquaintance Rape,” in Current Controversies in Family Violence, ed. Richard Gelles and Donileen Loseke (Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1993), pp. 120-32.

12. The passage is from Robin Warshaw, in her book I Never Called It Rape (New York: HarperPerennial, 1988), p. 2, published by the Ms. Foundation and with an afterword by Mary Koss. The book summarizes the findings of the rape study.

13. Newsweek October 25, 1993.

14. Naomi Wolf, The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women (New York: Doubleday, 1992), p. 166.

15. At the University of Minnesota, for example, new students receive a booklet called “Sexual Exploitation on Campus.” The booklet informs them that according to “one study [left unnamed] 20 to 25 percent of all college women have experienced rape or attempted rape.”

16. The Violence Against Women Act of 1993 was introduced to the Senate by Joseph Biden on January 21, 1993. It is sometimes referred to as the “Biden Bill.” It is now making its way through the various congressional committees. Congressman Ramstad told the Minneapolis Star Tribune (June 19, 1991), “Studies show that as many as one in four women will be the victim of rape or attempted rape during her college career.” Ramstad adds, “This may only be the tip of the iceberg, for 90 percent of all rapes are believed to go unreported.”

17. Gilbert, “Examining the Facts,” pp. 120-32.

18. Cited in Koss, “Hidden Rape,” p. 9.

19. Blade, special report, p. 5.

20. Ibid.

21. Koss herself calculated the new “one in nine” figure for the Blade, p. 5.

22. Cathy Young, Washington Post (National Weekly Edition), July 29, 1992, p. 25.

23. Katha Pollitt, “Not Just Bad Sex,” New Yorker, October 4, 1993, p. 222.

24. Koss, “Hidden Rape,” p. 16.

25. Blade, p. 5. The Blade reporters explain that the number vanes between one and twenty-two and one in thirty-three depending on the amount of overlap between groups.

26. “Rape in America,” p. 2.

27. Ibid., p. 15.

28. The secretary of health and human services, Donna Shalala, praised the poll for avoiding a “white male” approach that has “for too long” been the norm in research about women. My own view is that the interpretation of the poll is flawed. See the discussions in chapters 9 and 11.

29. Louis Harris and Associates, “The Commonwealth Fund Survey of Women’s Health,” p. 20.

30. Blade, p. 3.

31. Ibid., p. 6.

32. Ibid.

33. Dean Kilpatrick, et al., “Mental Health Correlates of Criminal Victimization: A Random Community Survey,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 53, 6 (1985).

34. Time, May 4, 1992, p. 15.

35. Blade, special report, p. 3.

36. Ibid., p. 3.

37. Ibid., p. 5.

38. Ibid., p. 3.

39. Camille Paglia, “The Return of Carry Nation,” Playboy, October 1992, p. 36.

40. Camille Paglia, “Madonna 1: Anomility and Artifice,” New York Times, December 14, 1990.

41. Reported in Peter Hellman, “Crying Rape: The Politics of Date Rape on Campus,” New York, March 8, 1993, pp. 32-37.

42. Washington Times, May 7, 1993.

43. Hellman, “Crying Rape,” pp. 32-37.

44 Ibid., p. 34.

45. Ibid., p. 37.

46. Katie Roiphe, The Morning After: Sex, Fear, and Feminism (Boston: Little, Brown, 1993), p. 45.

47. Blade, p. 13.

48. Andrea Parrot, Acquaintance Rape and Sexual Assault Prevention Training Manual (Ithaca, N.Y.: College of Human Ecology, Cornell University, 1990), p. 1.

49. Blade, p. 13.

50. Ibid., p. 14.

51. Alice Rossi, ed., The Feminist Papers: From Adams to de Beauvoir (New York: Columbia University Press, 1973), p. 414.

52. Katie Roiphe, “Date Rape’s Other Victim,” New York Times Magazine, June 13, 1993, p. 26.

53. Ibid., p. 40.

54. Women’s Studies Network (Internet: LISTSERV @UMDD.UMD.EDU), June 14, 1993.

55. Ibid., June 13, 1993.

56. See Sarah Crichton, “Sexual Correctness: Has It Gone Too Far?” Newsweek, October 25, 1993, p. 55.

57. See Neil Gilbert, “The Phantom Epidemic of Sexual Assault,” The Public Interest, Spring 1991, pp. 54-65; Gilbert, “The Campus Rape Scare,” Wall Street Journal, June 27, 1991, p. 10; and Gilbert, “Examining the Facts,” pp. 120-32.

58. “Stop It Bitch,” distributed by the National Clearinghouse on Marital and Date Rape, Berkeley, California. (For thirty dollars they will send you “thirty-four years of research to help refute him [Gilbert].”) See also the Blade, p. 5.

59. Sheila Kuehl, “Skeptic Needs Taste of Reality Along with Lessons About Law,” Los Angeles Daily Journal, September 5, 1991. Ms. Kuehl, it will be remembered, was a key figure in disseminating the tidings that men’s brutality to women goes up 40 percent on Super Bowl Sunday. Some readers may remember Ms. Kuehl as the adolescent girl who played the amiable Zelda on the 1960s “Dobie Gillis Show.”

60. International Crime Rates (Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1988), p. 1. The figures for 1983: England and Wales, 2.7 per 100,000; United States, 33.7 per 100,000 (p. 8). Consider these figures comparing Japan to other countries (rates of tape per 100,000 inhabitants):

FORCIBLE RAPE

U.S. 38.1

U.K. (England and Wales only) 12.1

(West) Germany 8.0

France 7.8

Japan 1.3

Source: Japan 1992: An International Comparison (Tokyo: Japan Institute for Social and Economic Affairs, 1992), p. 93.

61. “Men, Sex, and Rape,” ABC News Forum with Peter Jennings, May 5, 1992, Transcript no. ABC-34, p. 21.

62. Ibid., p. 11.

63. Ibid.

64. Senator Biden, cited by Carolyn Skomeck, Associated Press, May 27, 1993.

65. “The Violence Against Women Act of 1993,” title 3, p. 87.

66. Ruth Shalit, “On the Hill: Caught in the Act,” New Republic, July 12, 1993, p. 15.

67. See ibid., p. 14.

68. Stephen Donaldson, “The Rape Crisis Behind Bars,” New York Times, December 29, 1993, p. A11. See also Donaldson, “Letter to the Editor” New York Times, August 24, 1993. See, too, Wayne Wooden and Jay Parker, Men Behind Bars: Sexual Exploitation in Prison (New York: Plenum Press, 1982); Anthony Sacco, ed., Male Rape: A Casebook of Sexual Aggressions (New York: AMS Press, 1982); and Daniel Lockwood, Prison Sexual Violence (New York: Elsevier, 1980).

* Researching the “Rape Culture” of America

By Dr. Christina Hoff Sommers

As an associate professor of philosophy at Clark University, Dr. Christina Hoff Sommers specializes in contemporary moral theory. She has written articles for The New Republic, The Wall Street Journal, the Chicago Tribune, The Washington Post, and The New England Journal of Medicine.

**********************************************

If you contribute to other people's happiness you will find the true meaning of life. The key point is to have a genuine sense of universal responsibility.

**********************************************

If you contribute to other people's happiness you will find the true meaning of life. The key point is to have a genuine sense of universal responsibility.